2.0 “True” MOE Glulam:

When Incremental Gains Meet Real-World Design

It’s marketed as new and exciting, but is it?

When 2.0 “true” MOE glulam beams are marketed as a major performance advancement, it sounds like a big deal. Higher MOE means a stiffer beam and longer spans. Right? In real-world building applications, this opens the door to increased complexity for everyone involved — designers, manufacturers, distributors, lumberyards, even framers. Ultimately, this leads to confusion and higher costs across the board.

The difference isn’t what it seems.

Everything varies, especially wood. A beam labeled 2.0 “true” MOE represents a statistical average, not a guaranteed value. The number on the tag is not an absolute — and it behaves nearly the same as a 1.9 “true” MOE glulam in practice.

The challenges and tradeoffs outweigh the benefits.

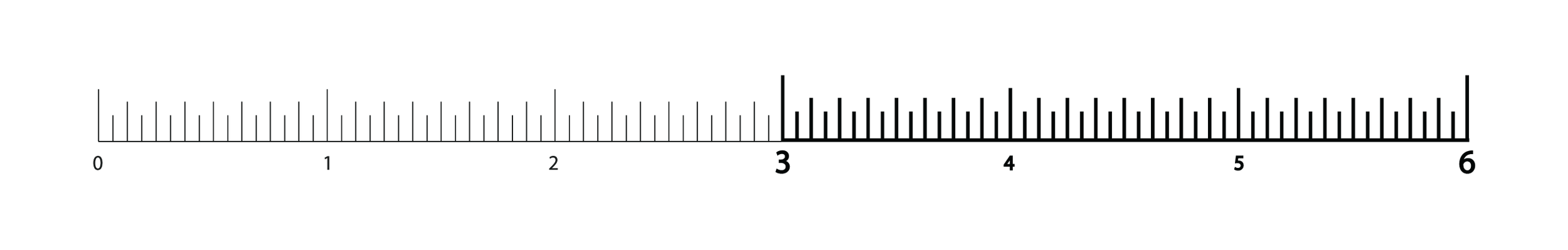

Adds only 3-6” in allowable span.

In most applications, the real-world difference translates to about 3 to 6 inches of additional allowable span, depending on loading and deflection limits. You’ll get more meaningful differences by changing depth rather than chasing MOE.

Higher costs for everyone.

You have to use a higher-grade tension lam to create a 2.0 “true” MOE beam, which is the hardest to source and more expensive. If you put more high-grade material into one beam, you’re spreading that resource less efficiently.

Let’s unpack what a 2.0 “true” MOE rating really means in practice.

-

The difference comes down to how deflection is calculated. With “true” MOE, you include shear deformation. With “apparent” MOE, you don’t. In common glulam practice, the accepted relationship is that “apparent” MOE is roughly 0.95 times the “true” MOE. So a 2.0 “true” MOE beam is roughly equivalent to a 1.9 “apparent” MOE beam.

Apparent MOE made hand calculations simpler. Traditional deflection equations use a single modulus value and the member’s moment of inertia. Before computers were widely used, most engineers didn’t want to add a second calculation for shear deflection. That practice stuck, and it works well.

-

A lot. With a coefficient of variation around 8–10%, the performance distributions for 1.9 and 2.0 “true” MOE beams overlap by about 80%.

That means most beams in those two grades behave nearly the same in practice. The number on the tag is just the average in the middle — not an absolute.

-

MOE is a serviceability issue, not a structural one. It impacts comfort and function. Does the floor bounce? Do cabinets rattle? Do doors and windows stick?

In most floor systems, it’s the joists or trusses that control how the space feels because they’re light and flexible. The supporting glulam beam is usually much wider and deeper, and resists deflection far more.

-

The bang for the buck is small. The ability to make a 2.0 “true” beam is available to all manufacturers under APA standards. APA has an approved layup that requires high-grading tension laminations. Those are the hardest to source. If you put more high-grade material into one beam, you’re spreading that resource less efficiently.

If only 10 percent of your lumber mix qualifies as tension-grade, you can either make two standard beams or one “premium” beam. To do it at scale, you have to source more high-grade lumber. That’s doable, but it costs more.

With the variability in the product, a 1.9 versus a 2.0 behaves almost the same to most people. A commonly referred to "1.8E" beam is, in fact, the APA's published 1.8 "apparent"/1.9 "true" 24F-V4 and 24F-V8 Douglas Fir glulam beams, the same ones that have been used for decades. The only difference in the published "apparent" and "true" MOE is in how allowable deflection is calculated. There is no actual physical difference in the beam or its performance.

-

Complexity. More grades increase the chance for mistakes. When one product doesn’t clearly outperform the other, that complexity is hard to justify.

Design workflows: Was the beam designed as a 1.9 or a 2.0? Was it designed using "apparent" or "true" MOE? How do I specify it correctly so I know I will get what I need in the field?

Field challenges: Do I have the correct beam? How do I know which one I have? Who do I call to find out?

Inventory: How do I manage inventory with increased complexity, carrying costs, waste, and handling risk? How do I manage customer requests to guarantee we provide the correct material?

-

Yes. It is technically higher. The chances of getting a slightly stiffer beam are better.

But the chances of anyone actually feeling that difference in a building are extremely small unless you’re doing a very controlled study. On paper, it looks meaningful. In the real world, with a material that varies by 10% or more, that 5% is trivial.

-

Most seasoned engineers won’t design that tight. They’ll add depth and build in margin so it doesn’t come back to haunt them. With the range in the product, a 1.9 versus a 2.0 “true” MOE is basically the same thing. If you want meaningful change, don’t chase 5 percent in MOE. Change the depth.

Architects, builders, and designers trust QB Corp.

Professional engineer Mike Baker has seen a lot of glulam beams and marketing claims over his four-decade-long career. Grounded in mechanics, statistics, and how structures actually behave in the field, get the full story on what 2.0 “true” MOE means to you from his expert point of view.

One of the largest CNC-equipped glulam manufacturers in the United States, QB Corp has been committed to excellence since 1977, with the capacity to produce over 1.5 million board feet of product per week with high reliability and performance.

Still have questions about MOE?

Every project is different, and marketing claims don’t always translate cleanly to the field. If you have questions or require guidance, we’ll give you a straight answer.